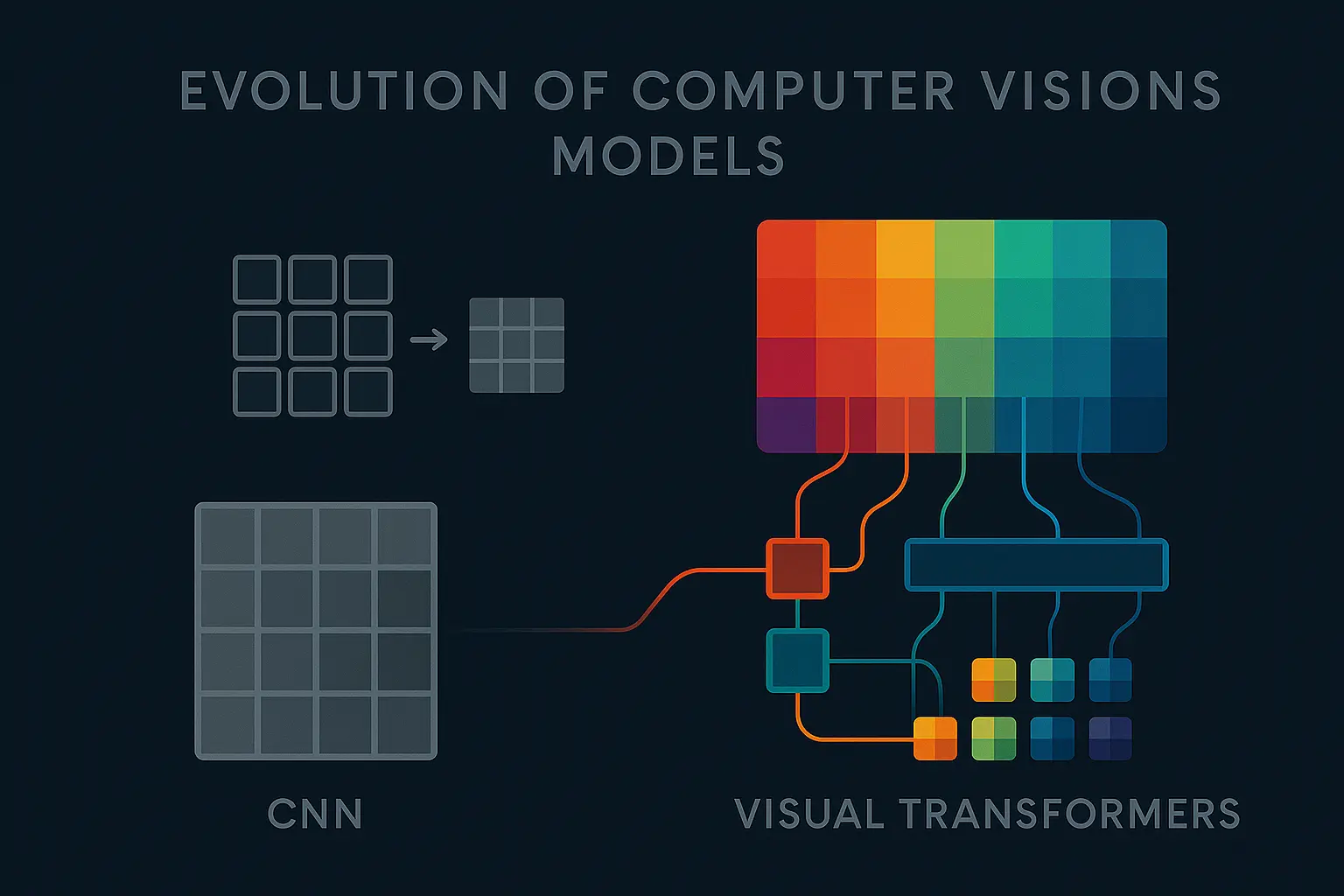

From CNNs to Visual Transformers: A Decade of Change in Computer Vision

As of 2025 , Visual Transformers seem to be the new gold standard in computer vision. Everyone’s talking about them but it’s interesting to look back and see how we got here.

The CNN Years

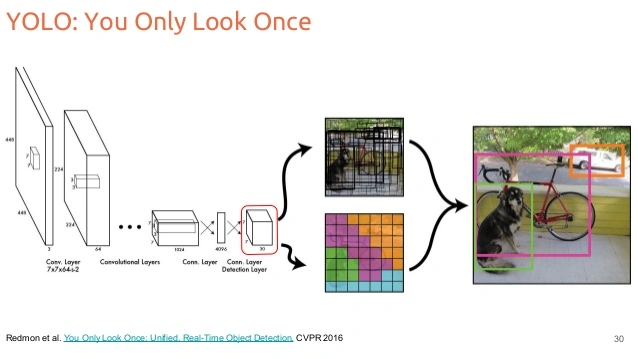

During the 2010s , we saw huge progress in computer vision. When AlexNet won the ImageNet challenge in 2011 , it basically kicked off the deep learning era for vision. From there, CNNs ruled everything. Research improved iteratively, with models like VGG , ResNet , and eventually YOLO , which made object detection practical for almost anyone.

I still think YOLO was a small revolution, plug-and-play object detection, open-source weights, easy fine-tuning, decent performance without needing a supercomputer. You could train it on your own dataset with a few dozen examples and get something working in days. That’s what made it so accessible for hobby projects and research prototypes.

Diagram showing how YOLO works

Diagram showing how YOLO works But there was always a bottleneck: the dataset .

A model only performs well if the dataset matches the conditions of the real environment where it’s used. For instance, imagine training YOLO to detect cats and dogs, but your dataset has 1 dog for every 9 cats . The model will probably learn “if it has four legs, it’s a cat,” and still reach 90% accuracy, technically good metrics, but useless in practice.

That’s an easy example, but things get messy when the classes are more subtle. Say you’re training a model to detect “prey” vs. “predator” animals. If you collect data in Europe, you’ll get foxes, rabbits, deer, etc. But your “worldwide prey” class will actually just represent European prey . The model will fail as soon as it sees a kangaroo or a jaguar. So to make it robust, you’d need to collect data everywhere , and then annotate it all by hand .

And annotation is another story. Bounding boxes, segmentation masks, labels… hours of human work for every thousand images. One sloppy box, and you’ve degraded the model’s performance. That’s the trade-off of supervised learning.

The Transformer Breakthrough

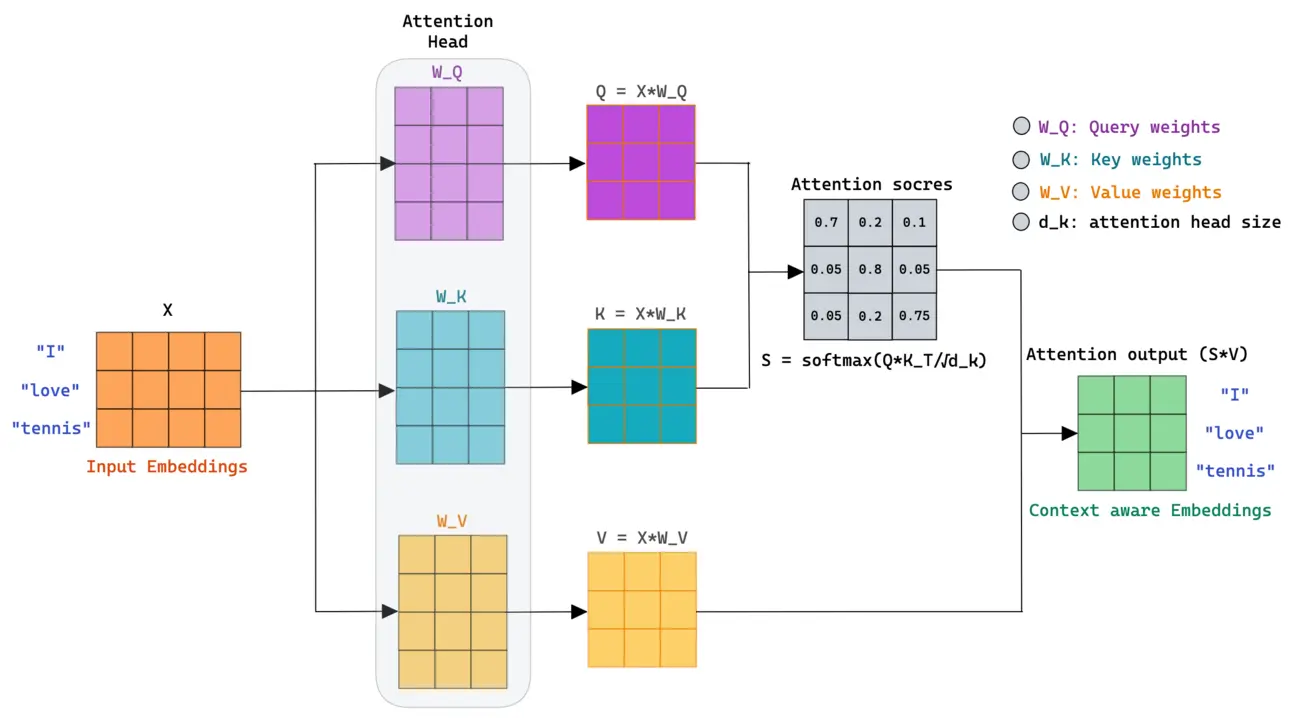

Then came 2017 , and the paper Attention Is All You Need . Transformers were originally a text model , and they changed everything, not by adding more convolution, but by removing it entirely.

Instead of local feature extraction, they used self-attention , letting the model decide what parts of the input are important. The result? Fewer handcrafted assumptions, more flexibility, and a structure that could scale with data.

Diagram of the attention block’s operation. Source: Mlspring

Diagram of the attention block’s operation. Source: Mlspring At first, Transformers were purely for language tasks , translation, summarization, text generation. But the idea quickly spilled over into vision.

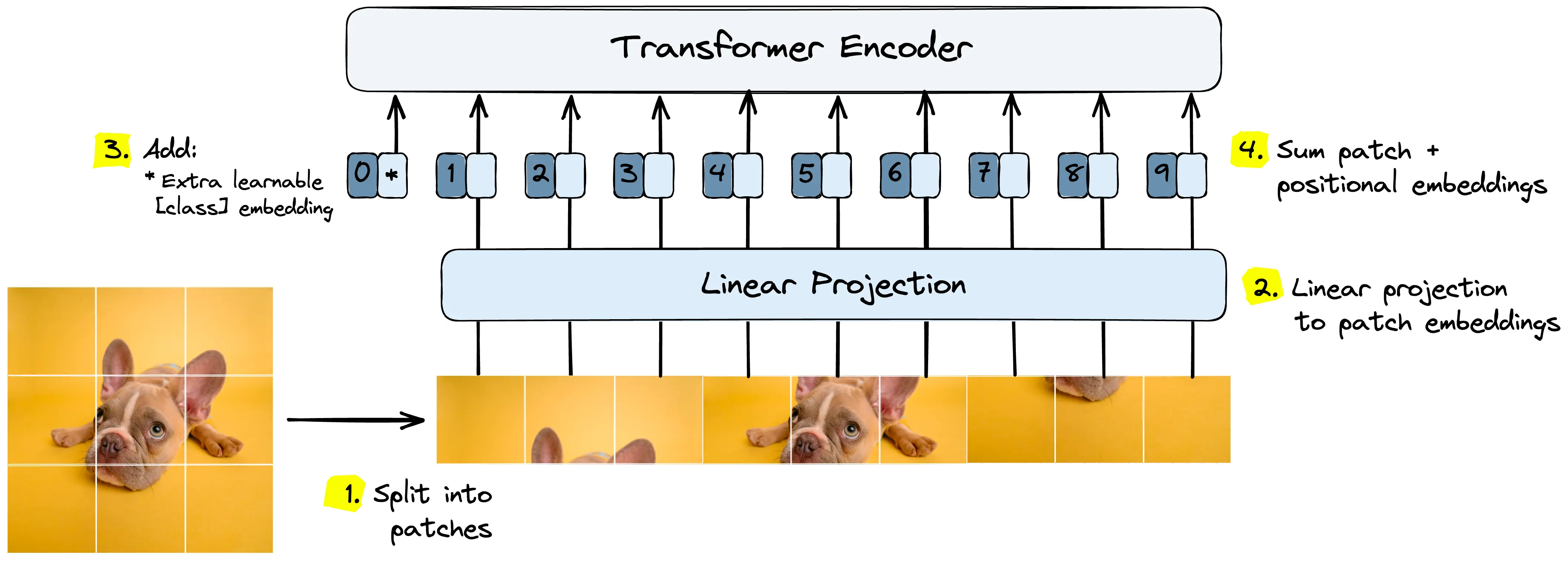

In 2019 , researchers started inserting self-attention blocks into ResNet-like architectures. And by 2020 , the Vision Transformer (ViT) appeared. It cut images into patches, treated them like words, and processed them with the same attention mechanism as in NLP. The result? State-of-the-art accuracy with enough data and compute.

ViT splits images into patches while preserving each patch’s spatial locality information

ViT splits images into patches while preserving each patch’s spatial locality information That’s when the game changed. Instead of manually engineering inductive biases like convolution kernels, the model could learn what mattered, if you had the GPU budget.

Enter Multimodality and Grounding DINO

Now, let’s fast-forward to what’s happening today: Grounding DINO and multimodal models .

Multimodality basically means mixing data from different domains, image + text, radar + vision, audio + text, and so on, to make the model smarter. When I was writing my master’s thesis in 2021 , this was already trending. I was asked to build a vision–radar dataset to train a Vision–Radar Transformer for 3D vehicle tracking. It was cool, but the big winner turned out to be text–vision models.

Here’s why.

If you show a picture of a sailboat to a vision-only model, it might label it as “boat.” That’s it. But if you combine it with a text model trained on the entire internet, it suddenly knows that a sail is usually white and sits above the hull , that both belong to a boat , and that a boat is used on water . That contextual bridge is what makes multimodal models so powerful, they understand concepts , not just pixels.

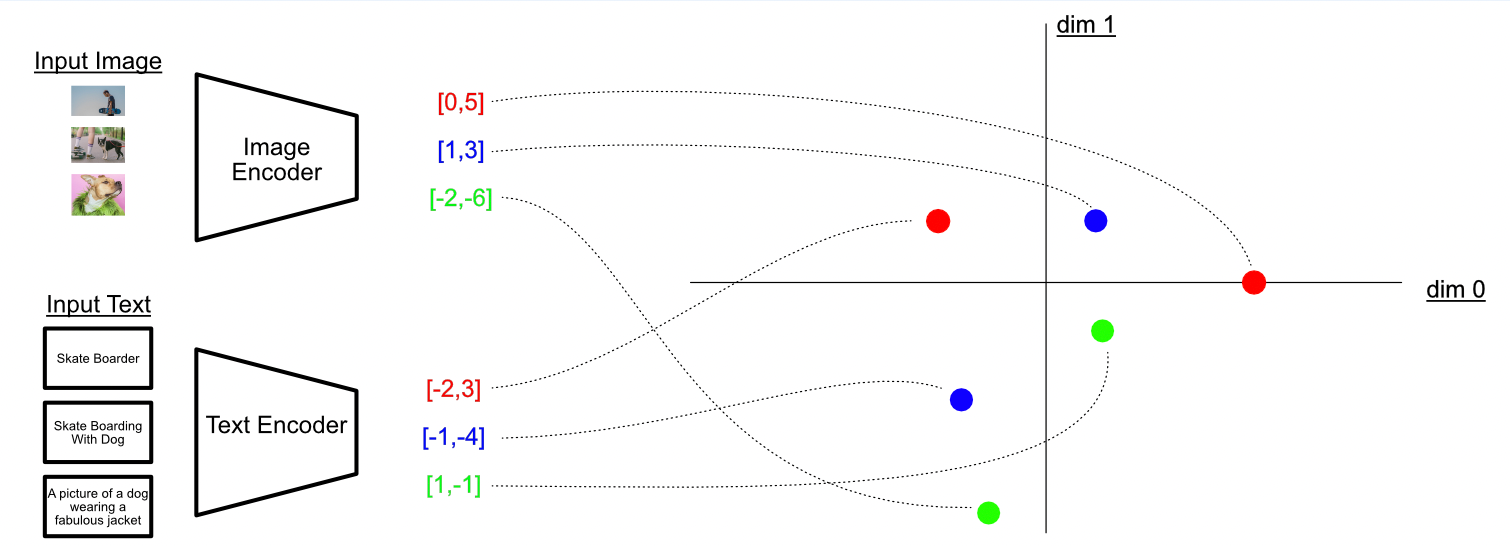

The CLIP model maps concepts extracted from images and text into the same latent space!

The CLIP model maps concepts extracted from images and text into the same latent space! Why It Actually Matters

The real impact is practical: We don’t need to manually annotate thousands of images for every new class anymore. As long as the concept exists in the text model (and isn’t too obscure), the model can detect it zero-shot , without retraining.

That means we’re no longer limited to the predefined classes from training. You can literally type what you want the model to find, and it will adapt in real time.

Here’s a quick experiment I ran: I used Grounding DINO on FPV drone footage and changed the target detection mid-video , it switched smoothly from detecting “painting” to “people” to “vr headset,” live.

Live demonstration of changing the detection classes on an FPV video

Live demonstration of changing the detection classes on an FPV video This kind of flexibility was unimaginable just a few years ago.

Where We Are Now

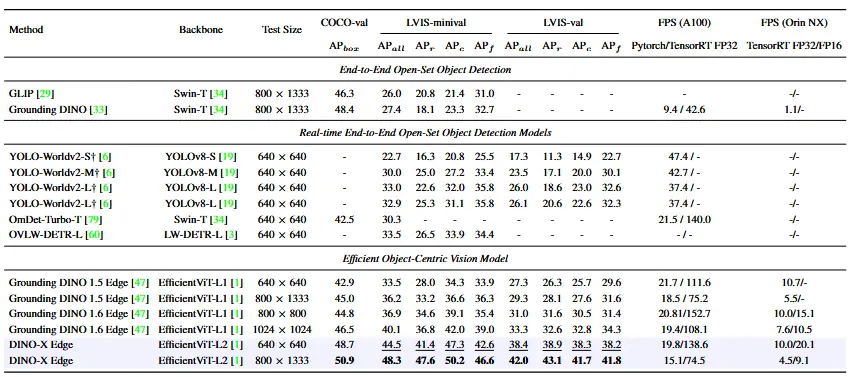

At the moment, Grounding DINO is one of the best open-source vision–language detectors you can run locally. There are newer variants like GroundingDINO 1.5 and GroundingDINO-X , but they’re closed-source , which makes them less interesting for experimentation.

Performance comparison between different open-source and closed models

Performance comparison between different open-source and closed models If the 2010s were about detecting things , the 2020s are about understanding them , and for the first time, models seem to actually get the context behind what they see.

From pixels to open-dictionnary human concept

From pixels to open-dictionnary human concept